A user-driven consent platform for health data sharing in digital health applications

We argue that a wide-scale adoption of the SHC platform would represent a major step toward a more transparent, user-centric approach to health data sharing. By replacing fragmented consent experiences with a single, structured interface, SHC empowers individuals to manage health data sharing across apps in a consistent and informed way. While SHC itself does not execute data transfers, it offers a trusted consent infrastructure, ensuring that sharing only occurs under clear user-defined conditions. Legal responsibility for secure and lawful data use remains with the individual health applications. In the future, national Health Data Access Bodies (HDAB), required under the EHDS Regulation will have an important governance and infrastructure role, including the processing data requests and issuing of permits as well as the provision of closed secure environments for data access (see Art. 57 (1) EHDS regulation)10. Health apps that collect and process electronic health data must implement robust technical and organizational safeguards to ensure compliance with the granted consent and regulatory requirements. HDAB will be responsible for verifying that data holders meet trustworthiness criteria, maintaining compliance with regulatory obligations, and continuously auditing access mechanisms. In addition, it will authorise data access only after a reviewed request has been found to match a verified and approved purpose. By establishing these multilayered safeguards, the SHC platform, alongside EHDS structures, promotes a secure, transparent, and user-centric model of health data sharing, ensuring that individuals retain control over their information while enabling valuable secondary use for research and public health advancements.

In a digitally connected healthcare system, where data is expected to flow seamlessly between patients, providers, and researchers, a robust consent infrastructure is essential. SHC not only supports personalisation and control, but also opens the door for integrating feedback mechanisms that foster user trust and engagement. Real-time audit trails and usage notifications can help inform users not just of intended, but of actual data use. Future integrations with technologies such as blockchain-based smart contracts or de-identified tokens could further enhance transparency29.

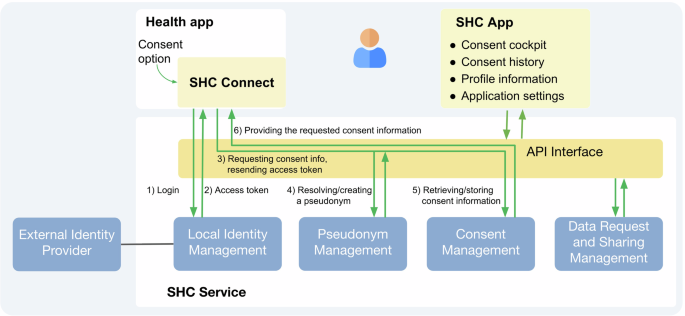

The design of SHC was informed by stakeholder and user feedback, and shaped by key implementation decisions across system architecture, governance, technical integration, and digital literacy. Table 3 summarises these considerations, which will guide future iterations. In a deliberate choice, we developed the SHC system as a centralised architecture. Centralisation enables direct assignment of responsibility for consent logic, secure identity management, and consistency across health apps. These properties are priorities for accountability, safety, timely deployment in app and consistent user experience. However, this model also introduces limitations, including the reliance on a single infrastructure and reduction in scalability. Ultimately, the SHC and decentralised models share the core principles of user control and empowerment and future work could explore decentralised or hybrid approaches for SHC.

A key challenge is maintaining user engagement without creating cognitive or administrative burden. Consent processes must be intuitive, yet meaningful, enabling users to exercise real control without being overwhelmed. Future research should explore how users interpret consent granularity, what levels of complexity they find acceptable, and how preferences evolve over time.

Legitimate concerns are raised about the low participation rates in consent-based systems and risk of mass withdrawal in opt-out. Both situations may reduce sample size and introduce bias, as individuals who decline consent or opt out might differ systematically from those who remain in the dataset. Compared to non-consent/no opt-out systems, lower sample sizes are to be expected leading to lower statistical power of analysis30. However, these risks can be mitigated through effective public engagement strategies, including broad awareness campaigns as well as tailored outreach to specific groups, such as minority populations who may have lower baseline trust or digital access. Information must be provided in accessible, relevant and trustworthy formats. A successful example is the “All of Us” Research Program by the National Institute of Health (NIH, USA), which enrolled over 650,000 participants, many from historically underrepresented groups, by partnering with community organizations, offering multilingual materials, and providing a transparent dashboard that shows how participant data is used. Additionally, statistical methods like raked weights can be applied to iteratively reweight the sample for specific variables (e.g., age, gender, ethnicity and others) to match the variables distribution in the reference population31. This enables statistically significant and relevant analyses without the need to include the entire population, as working with representative samples is a well-established and accepted practice in scientific research. Crucially, such engagement must be accompanied by a clear and enforceable data governance framework for secondary use, including transparency around data access by commercial entities to prevent public outcries as experienced in the UK17. Together, these measures can help establish a renewed social contract grounded in genuine public trust, informed decision-making, and voluntary participation.

The EU AI Act introduces transparency obligations for data used in training high-risk AI systems (Article 10), including requirements to document data sources, processing methods, and representativeness32. The SHC platform can support these obligations by offering user-specific consent records and auditable provenance of data shared from health apps. This strengthens legal and ethical accountability for AI development, reinforcing user trust and lawful data governance. This could underscore EU’s strong stance as a global leader in AI regulation, standing in harsh contrast to large-scale non-consent and non-transparent data scraping for Large Language Model developments we have seen so far33.

Based on the analysis of relevant regulatory frameworks and the development of the SHC platform, we propose a set of key recommendations as outlined in Table 4 to support the implementation of a standardised digital consent infrastructure. The recommendations summarise the importance of regulatory alignment, neutral governance, and technical interoperability to support a trusted consent infrastructure. User empowerment through granular, revocable consent and transparency mechanisms is essential for building public trust. Addressing consent bias and ensuring inclusive participation are critical for equitable and representative health data use.

In conclusion, standardised consent management offers a transformative approach to health data sharing from apps and wearables. Platforms like SHC enable dynamic, transparent, and user-driven consent processes. They create a scalable foundation for ethical, secure, and interoperable data sharing, balancing individual autonomy with the needs of healthcare and research. The future of health data governance will depend not only on legal frameworks, but also on empowering tools that make consent both meaningful and actionable for every user.

link