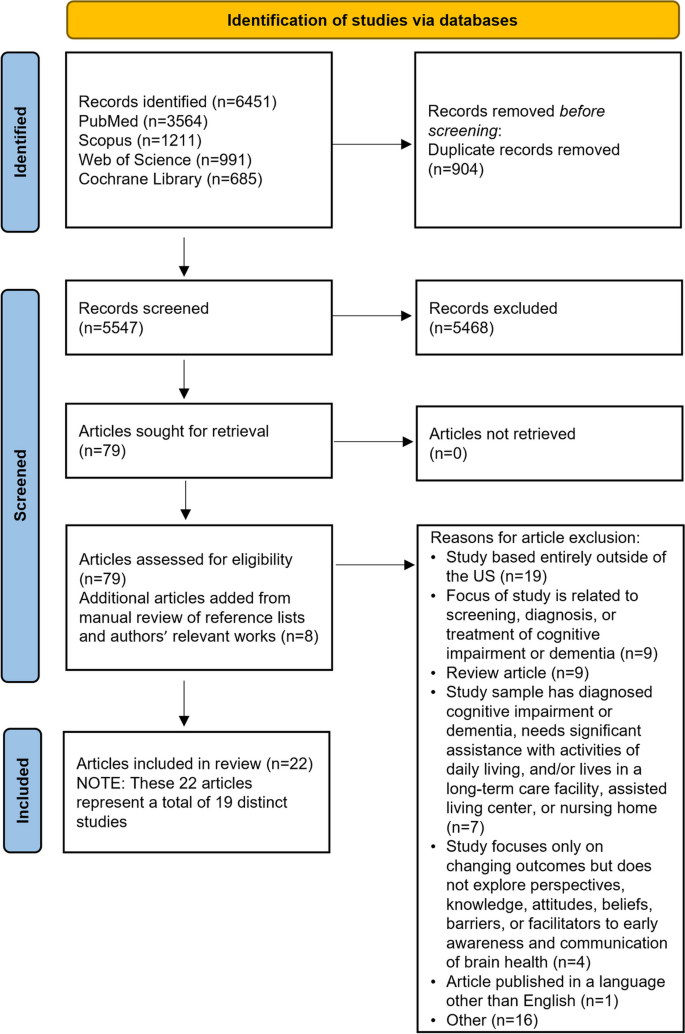

In total, 5547 unique records were identified. Of these, 5468 were excluded after title and abstract screening. Articles were excluded if they were published before the year 2000 or if they were published in a language other than English. Studies conducted outside the US were also excluded, as were those that focused on patients already diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease or mild cognitive impairment, or that described specialist clinicians practicing outside of primary care settings. Additionally, review articles and studies that did not explore perspectives, knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, barriers, or facilitators to communication related to brain health or cognitive concerns were also excluded. In total, 79 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility. A manual review of reference lists and key authors’ works led to the inclusion of another 8 articles. After screening, 22 articles representing 19 unique studies were identified for inclusion (Fig. 1).

PRISMA flow diagram. PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

Characteristics of included studies are detailed in Table 1. Studies explored either perceptions of cognition or provider-patient interactions in the context of a patient’s cognitive complaints. We found no articles that specifically explored preventive brain health conversations. Most were descriptive in nature, using qualitative, quantitative, or mixed-methods approaches. The most common methods of data collection included focus groups, semi-structured individual interviews, surveys, or a combination. Notably, most articles (n = 15) were published more than 10 years ago.

The majority of articles (n = 20) included lay participants (e.g., patients, caregivers, and community members); 4 included PCCs (e.g., physicians, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants). One study included both laypersons and PCCs [28]. Several studies specifically explored the beliefs, attitudes, and knowledge of US racial and ethnic minority groups: 2 each were conducted with Black/African American [29, 30] or Asian American participants [31, 32], 3 with Latino participants [33,34,35], and 2 with racially and ethnically diverse participants [36,37,38,39,40].

Overall, the quality of the studies was high. Using the MMAT to appraise the quality of the studies, we found that 15 of the 16 qualitative studies adequately met all criteria for methodological quality. [29,30,31,32,33, 35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44] Quality was more varied among quantitative descriptive studies [28, 45, 46], and the lowest quality studies included in this review used mixed methods designs [34, 47, 48]. Detailed quality assessment results can be found in Appendix C.

Our review uncovered 4 main themes that provide insight into barriers to and facilitators of implementing early conversations about brain health between PCCs and their patients.

Theme 1: PCCs are hesitant to discuss brain health and cognitive concerns

Studies addressed discussions of cognitive concerns or impairment, rather than brain health as a general category of health or wellness. Many PCCs are uncomfortable discussing cognitive concerns with their patients, or lack resources and support for these conversations [47]. In a survey of 972 physicians, approximately half of whom were family or general practitioners, 31.9% of respondents reported that lack of reimbursement was the most frequent barrier to discussing cognitive impairment with patients [45]. Other barriers commonly reported by respondents included a lack of proven treatments and limited scientific evidence for prevention of MCI or ADRD (26.3%) and the need to address more pressing medical issues (24.6%) [45]. A qualitative study of 49 PCCs reported additional barriers to talking about cognition, such as a lack of time during appointments, therapeutic nihilism, insufficient evidence regarding prevention and treatment of cognitive impairment, and negative patient attitudes about cognition education [42]. Although these studies were conducted before the 2011 introduction of the Annual Wellness Visit, a preventive Medicare benefit that requires identification of any existing cognitive impairment [49], there is little evidence to suggest that PCCs’ attitudes and practices have dramatically changed.

According to the articles included in the present review, addressing these barriers would require resolving constraints related to time, clinic resources, and reimbursement; tailoring education to improve PCCs’ comfort and cultural awareness around discussing cognitive difficulties and interventions with their patients; and increasing their confidence in the evidence supporting the value of interventions. In a study of PCCs across 3 states, practitioners reported using a variety of sources, such as continuing medical education, popular media, and online resources to educate themselves on brain health [48], a finding corroborated by another study [45]. Effective dissemination of educational material related to brain health, cognition, and cognitive disorder care can and should occur through multiple approaches (e.g., online sources, continuing medical education, and professional journals). Strategies for establishing effective collaboration between PCCs and cognitive disorder specialists—who are scarce in many regions—have not yet been described in the literature. Productive areas for exploration include how best to facilitate knowledge transfer, how to provide PCCs with up-to-date understanding of interventions usable in primary care settings [48], and how best to define the clinical contributions of generalists and specialists in the evaluation and care of people with cognitive impairments.

Theme 2: patients are hesitant to raise cognitive concerns

In a study of older, primarily White patients attending a first visit to an outpatient geriatric practice, patients identified several barriers to discussing cognitive concerns with their physician [47]. Most often, patients felt it was the physician’s responsibility to initiate the discussion. Others intended to initiate the conversation during the appointment but forgot. In this same study, researchers noted that some patients may hesitate to raise cognitive concerns due to feelings of embarrassment or shame, resulting from stigma surrounding MCI and ADRD [47]. The role of stigma was also reported in a study of ethnically diverse older adults [38]. In that study, 42 focus groups were conducted with older adults representing 6 racial and ethnic groups (i.e., African American, Native American, Chinese American, Latino, White, and Vietnamese American). Researchers found that Native American, Chinese American, and Vietnamese American respondents were specifically concerned about stigma associated with MCI or ADRD and how stigma may impact their family relationships [38]. Two other studies suggested that individuals may not distinguish normal aging from cognitive decline [32, 41]. For example, in a study of 62 older Asian American participants, 95% of participants assumed that memory loss was part of normal aging [32].

The studies included in the present review also highlighted the need for solutions that address patients’ hesitance to initiate important brain health discussions and provided examples of such solutions. For instance, if patients believe it is the responsibility of their PCC to start discussions regarding cognition and if patients are likely to forget to raise cognitive concerns during appointments, then PCCs can remove this barrier by taking the lead [47]. However, as mentioned previously, PCCs are also often hesitant to start these conversations [42, 45, 47, 48]. One approach to successful, practical implementation is to treat discussions of cognitive concerns as routine by embedding questions around cognition within a medical review of systems [47]; however, additional resources are clearly needed to aid clinicians in leading these conversations.

Theme 3: evidence to guide clinicians in developing treatment plans that address cognitive decline is often poorly communicated

Both lay media and scientific discussions of brain health are often confusing, contradictory, or limited [30, 36,37,38, 48]. Thus, although most people recognize the importance of aging well and maintaining brain health [28, 30,31,32,33,34, 36, 37, 39,40,41, 48, 50], many remain skeptical of brain health research and unsure about which cognitive interventions are worthwhile, leading to therapeutic nihilism [43, 44, 46]. This theme was common across multiple studies reviewed. To date, no study has addressed whether the perception of ADRD as a disease that affects only elderly individuals may have promoted catastrophic thinking and reinforced avoidance on the part of both clinicians and their patients. In addition, many publications have described ADRD as a “terminal illness” rather than a manageable chronic condition [51,52,53]. Although this characterization may have been intended to elevate the importance of ADRD in public and medical discourse, this portrayal may have reinforced fear and avoidance.

To facilitate action around brain health, the studies included in the present review suggest that both laypersons and PCCs should be educated on the existing evidence that supports a range of interventions for brain health and cognitive disorders [29, 50]. This education should be communicated clearly, concisely, and consistently [30, 33, 43].

Theme 4: social and cultural context influence perceptions of brain health and cognition, and therefore affect clinical engagement

Several studies found that differences in beliefs about brain health and cognitive decline among racial and ethnic minority groups could be attributed to cultural differences. For example, in one study, Black people—and particularly Black women—were more likely to use language expressing spiritual elements when discussing brain health and concerns about cognitive decline; this fact highlights the importance of recognizing differences in the way individuals frame their concerns; one study suggests that Black women may respond more positively to messages that incorporate spiritual ideas [30]. Similarly, in 2 other studies, Latin American participants expressed spiritual and supernatural ideas related to brain health and cognitive decline [34, 35]. Both studies highlighted the value of collaborating with faith-based organizations to more effectively tailor messages for Latin American populations, and emphasized references to prayer, church-going, gratitude to a higher power, and a connection with God [35]. One study found beliefs and knowledge about memory loss differed across and within Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) participants, and these beliefs were informed by the unique social and structural factors of each AAPI ethnic group [32]. Immigration status and language barriers among various AAPI groups were also found to limit opportunities to engage in social and economic activities in the US, leading to a need for messaging that is not only culturally sensitive but that can also help surmount barriers to accessing appropriate health care [32]. On the other hand, another study found that Filipino American individuals often have a strong biomedical understanding of brain health through workplace exposure to individuals with cognitive impairment; many are employed in healthcare professions, including in long-term care [31].

Among laypersons, sex and gender may also play a role in conceptions of brain health and behaviors to maintain or improve brain health. Women often take the lead in providing healthcare information for their families, highlighting the need to specifically engage this population in early conversations on brain health [44]. Societally influenced traditional gender roles also appeared to affect specific beliefs and behaviors related to cognition. For example, while both women and men understood the importance of physical exercise and social engagement for maintaining cognitive functioning, women endorsed social and physical activities like group exercise classes, whereas men indicated that manual labor and formal employment could fulfill physical exercise and social needs [44].

The studies included in the present review also highlight that conversations around cognition should be tailored to specific patients and audiences, include culturally relevant information, and consider both the social and cultural contexts in which patients live [29,30,31, 37, 39]. The literature also reveals that primary care is just one setting in which to circulate this information; partnering with local communities’ trusted media sources and institutions is important for disseminating brain health messages [31, 33].

link